Eadweard Muybridge – the father of moving pictures

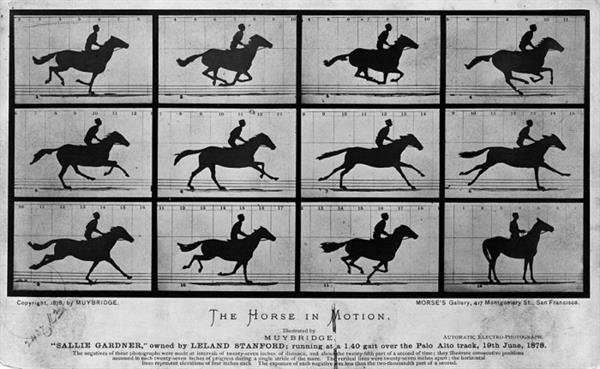

Here is the story behind the world’s first motion picture - The Horse in Motion that took birth one hundred and forty-three years ago (143).

Eadweard Muybridge – the pioneer of moving pictures

Today on June 15 1878 – the pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, original name Edward James Muggeridge, (born April 9, 1830, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, England) made history at a racetrack in Palo Alto, California.

Eadweard Muybridge English photographer important for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion and in motion-picture projection, photographed a horse in different stages of its gallop –The Horse in Motion.

How Eadweard Muybridge achieved the milestone - The Horse in Motion

In 1872, the former governor of California, Leland Stanford, a businessman and race-horse owner, hired Muybridge for a portfolio depicting his mansion and other possessions, including his racehorse Occident.

Stanford also wanted a proper picture of the horse at full speed and was frustrated that the existing depictions and descriptions seemed incorrect. The human eye could not fully break down the action at the quick gaits of the trot and gallop. Up until this time, most artists painted horses at a trot with one foot always on the ground; and at a full gallop with the front legs extended forward and the hind legs extended to the rear, and all feet off the ground.

Muybridge eventually managed to shoot a small and very fuzzy picture of Occident running in 1873. They agreed it lacked quality, but Stanford was excited to finally have a reliable depiction of a running horse. No copy of the image has yet resurfaced. Muybridge promised to study better solutions.

In July 1877, Muybridge made a new picture of Occident at full speed, with improved techniques and a much clearer result. To enhance the still fuzzy picture, it was recreated by a retouch artist and published as a cabinet card. The news about this breakthrough in instantaneous photography was spread enthusiastically, but several critics believed the heavily manipulated image could not be a truthful depiction of the horse. Muybridge allowed reporters to study the original negative, but as he and Stanford were planning a new project that would convince everyone, they saw no need to prove that this image was authentic. The original negative has not yet resurfaced.

In June 1878, Muybridge created sequential series of photographs with a battery of 12 cameras along the race track at Stanford's Palo Alto Stock Farm (now the campus of Stanford University). The shutters were automatically triggered when the wheel of a cart or the breast or legs of a horse tripped wires connected to an electromagnetic circuit. For a session on 15 June 1878, the press and a selection of turf men were invited to witness the process. An accident with a snapping strap was captured on the negatives and shown to the attendees, convincing even the most sceptical witnesses.

Reaction

The news of this success was reported worldwide. The Daily Alta California reported that Muybridge first exhibited magic lantern slides of the photographs at the San Francisco Art Association on 8 July 1878. Six different series were soon published, as cabinet cards entitled The Horse in Motion. Scientific American was among the publications at the time that carried reports and engravings of Muybridge's ground-breaking images.

Many people were amazed at the previously unseen positions of the horse's legs and the fact that a running horse at regular intervals had all four hooves in the air. This did not take place when the horse's legs were extended to the front and back, as imagined by contemporary illustrators, but when its legs were collected beneath its body as it switched from "pulling" with the front legs to "pushing" with the back legs.

Further developments

In 1879, Muybridge continued with additional studies with 24 cameras and published a very limited-edition portfolio of the results.

Muybridge had images from his motion studies copied in the form of silhouettes onto a disc, to be viewed in the machine he had invented, which he called a "zoopraxiscope". This device was later regarded as an early movie projector and the process as an intermediate stage toward motion pictures or cinematography.

During his later years, Muybridge gave many public lectures and demonstrations of his photography and early motion picture sequences, returning frequently to England and Europe to publicise his work. He also edited and published compilations of his work, which greatly influenced visual artists and the developing fields of scientific and industrial photography. He returned to his native England permanently in 1894. In 1904, Kingston Museum was opened in his hometown and continues to house a collection of his works to this day in a dedicated 'Muybridge Exhibition'.

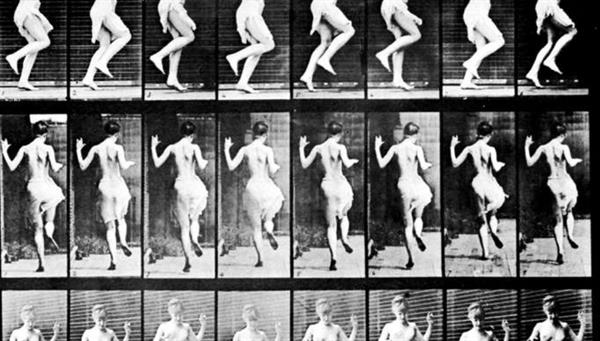

Eadweard Muybridge: Figure Hopping phenomenon

Muybridge made his most important photographic studies of motion from 1884 to 1887 under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania. These consisted of photographs of various activities of human figures, clothed and naked, which were to form a visual compendium of human movements for the use of artists and scientists. Many of these photographs were published in 1887 in the portfolio Animal Locomotion: An Electro-Photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Movements. Muybridge continued to publicize and publish his work until 1900, when he retired to his birthplace.

San Francisco panorama

In 1878, Muybridge made a notable 13-part 360° photographic panorama of San Francisco. He presented a copy to the wife of Leland Stanford. Today, it can be viewed on the Internet as a seamlessly-spliced panorama, or as a QuickTime Virtual Reality (QTVR) panorama.

More on Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge (born Edward James Muggeridge) was born in Kingston upon Thames in the United Kingdom, at age 20 he emigrated to America as a bookseller, first to New York, and then to San Francisco. Planning a return trip to Europe in 1860, he suffered serious head injuries in a stagecoach crash in Texas.

He spent the next few years recuperating in Kingston upon Thames, where he took up professional photography, learning the wet-plate collodion process, and secured at least two British patents for his inventions.

He went back to San Francisco in 1867. In 1868 he exhibited large photographs of Yosemite Valley, which made him world-famous.

In 1874 Muybridge shot and killed Major Harry Larkyns, his wife's lover, but was acquitted in a jury trial on the grounds of justifiable homicide.

Legacy left by the legend Eadweard Muybridge

Today, Muybridge is known for his pioneering work on animal locomotion in 1877 and 1878, which used multiple cameras to capture motion in stop-motion photographs, and his zoopraxiscope, a device for projecting motion pictures that pre-dated the flexible perforated film strip used in cinematography.

In the 1880s, he entered a very productive period at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, producing over 100,000 images of animals and humans in motion, capturing what the human eye could not distinguish as separate movements.

During his later years, Muybridge gave many public lectures and demonstrations of his photography and early motion picture sequences, returning frequently to England and Europe to publicise his work. He also edited and published compilations of his work, which greatly influenced visual artists and the developing fields of scientific and industrial photography. He returned to his native England permanently in 1894. In 1904, Kingston Museum was opened in his hometown and continues to house a collection of his works to this day in a dedicated 'Muybridge Exhibition'.

Muybridge died on 8 May 1904 in Kingston upon Thames of prostate cancer at the home of his cousin Catherine Smith.

His body was cremated, and its ashes interred in a grave at Woking in Surrey. On the grave's headstone his name is misspelled as "Eadweard Maybridge"

In 2004, a British Film Institute commemorative plaque was installed on the outside wall of the former Smith house, at Park View, 2 Liverpool Road.

Many of his papers and collected artefacts were donated to Kingston Library, and are currently under the ownership of Kingston Museum in his place of birth.